There was a time when being a .NET developer mostly meant writing solid C# code, building APIs, and shipping features. If the application worked and the database queries were fast enough, the job was done.

That world is gone.

In 2026, a modern .NET developer isn’t just a coder. They’re a system builder, balancing application development, cloud architecture, DevOps, security, and increasingly, AI-driven decisions.

One Feature, Many Disciplines

Consider a typical modern feature:

- A scheduled job populates data into a database.

- That data feeds reporting tools like Power BI.

- Deployment pipelines push updates across environments worldwide.

- Cloud services scale automatically under load.

- Monitoring and security controls are part of the delivery.

One feature now touches multiple domains. Delivering it requires understanding infrastructure, automation, data, deployment, and operations—not just application logic.

The scope of the role has expanded dramatically.

Fundamentals Still Matter

Despite all the change, the core skills haven’t disappeared.

Developers still need to:

- Build REST APIs that handle real-world load

- Write efficient Entity Framework queries

- Understand async/await and concurrency

- Maintain clean, maintainable codebases

Bad fundamentals still break systems, regardless of how modern the infrastructure is.

But fundamentals alone are no longer enough.

Cloud Decisions Are Now Developer Decisions

In many teams, developers now influence—or directly make—architecture decisions:

- Should this workload run in App Service, Containers, or Functions?

- Should data live in SQL Server or Cosmos DB?

- Do we need messaging via Service Bus or event-driven patterns?

These choices affect cost, scalability, reliability, and operational complexity. Developers increasingly need architectural awareness, not just coding ability.

DevOps Is Part of the Job

Deployment is no longer someone else’s responsibility.

Modern developers are expected to:

- Build CI/CD pipelines that deploy automatically

- Containerize services using Docker

- Ensure logs, metrics, and monitoring are available

- Support production reliability

The boundary between development and operations has largely disappeared.

Security Is Developer-Owned

Security has shifted left.

Developers now regularly deal with:

- OAuth and identity flows

- Microsoft Entra ID integration

- Secure data handling

- API protection and access control

Security mistakes are expensive, and modern developers are expected to understand the implications of their implementations.

AI Changes How We Work

Another shift is happening quietly.

In the past, developers searched for how to implement something. Today, AI tools increasingly help answer higher-level questions:

- What are the long-term tradeoffs of this architecture?

- How will this scale?

- What operational risks am I introducing?

The developer’s role moves from solving isolated technical problems to designing sustainable systems.

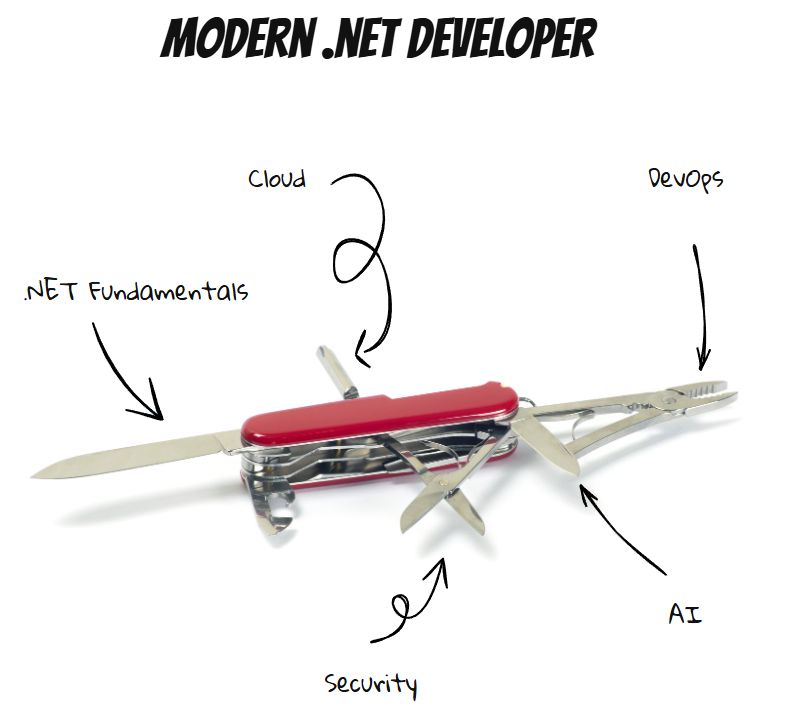

From Specialist to Swiss Army Knife

The modern .NET developer is no longer just a backend specialist. They are expected to be adaptable:

- Application developer

- Cloud architect

- DevOps contributor

- Security implementer

- Systems thinker

Not every developer must master every area—but awareness across domains is increasingly required.

The New Reality

The job has evolved from writing features to building systems.

And while that can feel overwhelming, it’s also exciting. Developers now influence architecture, scalability, reliability, and user experience at a system-wide level.

The industry hasn’t just changed what we build.

It’s changed what it means to be a developer.

And in 2026, being versatile isn’t optional—it’s the job.